Review - A Poet

Starring Ubeimar Rios, Rebeca Andrade, Guillermo Cardona, Alisson Correa. Written and directed by Simón Mesa Soto. 123 minutes. Unrated. In theaters.

Oscar Restepro is a poet. Not that we see him writing or reading poetry. In fact, the one time he’s asked to give a public reading of his work, Oscar’s rambling, argumentative preamble goes on for so long he’s cut off by the moderators before he gets around to the poem itself. See, Oscar has a lot of thoughts about a poet’s role in society and the tradition of noble suffering for one’s art. He often ends up shouting these theories at his drunken buddies until all hours of the morning. Sometimes he wakes up on the sidewalk.

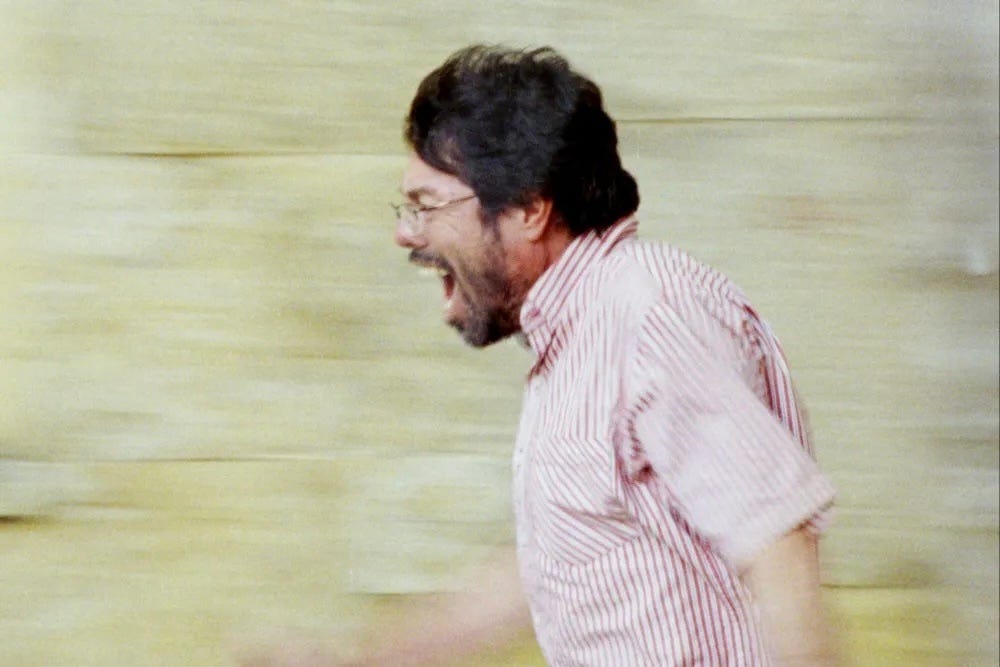

The protagonist of Colombian writer-director Simón Mesa Soto’s bruisingly funny tragicomedy is played by first-time actor Ubeimar Rios. He’s a fascinating physical specimen who appears to have been put together out of mismatched parts. With arms too short for his body and a mouth too big for his face, Oscar slumps and slouches even when he isn’t hammered, his clothes an unkempt mess of wrinkles and dandruff. Yet however awkward and off-putting, Rios imbues him with a shabby nobility. We can believe that Oscar wasn’t always like this. We see how he might once have had a wife, a child and published two well-received books of poetry, before he hit the skids.

These days the divorced and unemployable Oscar crashes with his ailing mother. His brother-in-law can’t wait to kick him out and sell the house when she dies. His estranged teenage daughter is headed off to college soon, and despite being proudly penniless, Oscar has promised to pay her tuition. His sister calls in some favors in a last ditch attempt to help her hapless brother by getting him a gig teaching writing at the local high school. We think we know how this is all going to go when we see Oscar topping off his coffee thermos with booze.

But then he meets Yurlady (Rebeca Andrade), a 15-year-old student who writes beautiful, simple poems in a lavishly illustrated notebook. She shows great promise, and with the right guidance could really be going places. Oscar sees Yurlady not just as a possible protégé, but also an opportunity to fix all the mistakes he’s made with his own daughter. The kicker is, she’s not particularly interested in poetry. And to be fair, the way Oscar describes an artist’s life of toil and sacrifice sounds pretty dismal to a teenage girl. Yurlady really just wants to get a steady job to help support her struggling family and to have some babies of her own. The whole poetry thing is his dream, not hers.

It’s a cutting twist on the inspirational teacher formula, with the mentor far more invested than the mentee. “A Poet” becomes even more ruthlessly amusing when Oscar introduces Yurlady to a local poetry collective run by his preening, more successful rival Efrian, played with slick disingenuousness by Guillermo Cardona. Efrian sees Yurlady not as an artist, but as an irresistible hook for donors. (He implores her to play up her impoverished background in the poems so people will feel better about themselves for giving money.) Soto has a good time skewering the art scene’s performative social justice bent, like at a champagne reception when we overhear a female poet and an indigenous writer arguing bitterly over whose people have had it worse.

More than once during “A Poet” I thought of Llewyn Davis, the moderately talented, extravagantly unlucky troubadour knocking around the fringes of the 1960s folk scene in the Coen brothers’ 2013 masterpiece, “Inside Llewyn Davis.” It’s my favorite of their films, and may very well be the definitive statement about loving an art form that doesn’t love you back. (There was a time in my life when my personal circumstances had become uncomfortably close to Llewyn’s, and I was watching the movie entirely too often. I had to put it away for a few years there because it was hitting to close to home. I’m happy to report that we’re past all that now. I hope.)

Like Llewyn, Oscar is often the author of his own misery. The more we hear his manifestos about the things an artist must sacrifice, the more they start to sound like justifications for how badly he’s screwed up his life. But Soto is a good deal more sentimental than the Coens, and the film turns disappointingly squishy in the final scenes, dangling hope and redemption instead of an ironic fait accompli. Much like Yurlady, the film ultimately settles for conventional prose.

“A Poet” is now playing at the AMC Boston Common.